Six days after the court ruling finding Google illegally monopolized digital advertising markets, both sides have submitted dramatically different proposals for how to remedy the situation, setting up a consequential battle over the future of online advertising.

On April 17, 2025, Judge Leonie Brinkema of the Eastern District of Virginia ruled that Google violated Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act by monopolizing key digital advertising technology markets. Now, the remedies phase has begun, with the Department of Justice and state plaintiffs seeking the breakup of Google's ad tech business, while Google proposes behavioral remedies it claims would address competitive concerns without dismantling its products.

The court's findings

Judge Brinkema's 115-page ruling found Google guilty of monopolizing two critical markets in digital advertising: publisher ad servers and ad exchanges for open-web display advertising. The court determined Google held a 91% share of the publisher ad server market and systematically leveraged its control across different parts of the ad tech ecosystem to eliminate competition.

According to the court's opinion, Google engaged in a "decade-long campaign of exclusionary conduct" to "acquire," "protect," and "entrench" monopoly power. The ruling identified several specific anticompetitive practices Google employed:

- Tying its ad exchange (AdX) to its publisher ad server (DFP) through technical and policy restrictions

- Implementing a feature called "First Look" that gave AdX preferential access to publisher inventory

- Creating a "Last Look" advantage that allowed Google to win auctions by minimal amounts

- Imposing "Unified Pricing Rules" that prevented publishers from charging Google higher prices than its competitors

The court found these practices allowed Google to charge "durable supracompetitive prices" in the ad exchange market "for well over a decade."

Competing remedy proposals

The stark differences between Google's and the government's proposed remedies highlight the enormous stakes in this case. Their filings submitted on May 5, 2025, present fundamentally different approaches to addressing the antitrust violations.

The government's proposal: Structural separation

The Department of Justice and state plaintiffs have proposed a sweeping set of remedies centered around divestiture—forcing Google to sell off key parts of its advertising technology business. Their plan includes:

- Complete divestiture of Google's ad exchange (AdX)

- Phased divestiture of Google's publisher ad server (DFP), beginning with open-sourcing the auction logic, then selling the remaining parts

- Prohibitions against Google using its advertising data across products

- Requirements to share certain data with competitors

- Appointment of trustees to monitor Google's compliance

According to the government's filing, "This comprehensive set of remedies—including divestiture of Google's unlawfully obtained monopolies and the products that were the principal instruments of Google's illegal scheme—is necessary to terminate Google's monopolies, deny Google the fruits of its violations, reintroduce competition into the ad exchange and publisher ad server markets, and guard against reoccurrence in the future."

The government argues that divestiture is the "most important" and "most effective" antitrust remedy because it is "simple, relatively easy to administer, and sure." They cite Supreme Court precedent stating that courts should "start from the premise that an injunction against future violations is not adequate to protect the public interest."

During a May 2 hearing, government attorneys told the court there are "tons of cases, Supreme Court cases that talk about the need for divestiture," and argued the law allows divestiture "even when that asset may have been lawfully acquired to begin with."

Google's proposal: Behavioral remedies

Google has offered a dramatically different approach, proposing behavioral remedies that would change how its products operate without breaking up its business. Google's proposal includes:

- Making real-time bids from AdX available to all rival publisher ad servers

- Removing Unified Pricing Rules to allow publishers to set different price floors for different bidders

- Committing not to rebuild "First Look" or "Last Look" features

- Appointment of a trustee to monitor compliance for three years

In its filing, Google argues these changes would "fulfill the Court's mandate 'to redress the violations' found and 'restore competition'" without disrupting markets beyond those affected by the violations. Google claims its proposal "would promote competition on the merits between Google and its rivals for publisher business."

During the May 2 hearing, Google noted that government attorneys conceded Google's proposal "would absolutely address our concern about the prior illegal conduct."

Google further contends that divestiture is "legally unavailable" because this is not a case involving an unlawful merger or acquisition. The company cites the Microsoft antitrust case, where an initial divestiture order was reversed on appeal, as precedent that divestiture is ordered "[b]y and large" only in cases involving "the dissolution of entities formed by mergers and acquisitions."

Technical challenges of divestiture

A significant portion of Google's filing addresses the technical difficulties of divesting its advertising products. The company argues that its ad exchange and publisher ad server have been "closely integrated with—and entirely dependent on—Google's internal proprietary software and hardware infrastructure for nearly two decades."

According to Google, divesting either product would require "developing and creating fully new versions" capable of working outside Google's infrastructure, a project it estimates would take "at the very minimum five years, but likely considerably more time—even as much as one-and-a-half times to twice as long—even with hundreds of qualified software engineers."

Google also raises concerns about who would purchase these products, noting that witnesses at trial did not testify that rivals are interested in running AdX or DFP given the "extremely major investment" and "significant operational support, infrastructure, and capital resources" required.

Industry implications

The outcome of this remedies phase will have profound implications for digital advertising markets that fund much of the free content available online. As Judge Brinkema noted in her opinion, "digital advertising has been the lifeblood of the Internet, funding much of its development while providing free access to an extraordinary quantity of content and services."

For publishers who have relied on Google's advertising technology, any remedy will require adaptation. Publishers have long complained about their dependence on Google's tools, with witnesses at trial testifying about their inability to switch away from Google despite dissatisfaction. News Corp executive Tom Layser testified: "I would like Google to pass the publisher a real-time price." Daily Mail executive Nick Wheatland stated the company couldn't switch to other publisher ad servers because "we still needed to access AdX demand, so we still had to use Google's publisher ad server."

The court found that Google's practices allowed it to charge supracompetitive fees that have persisted for over a decade. The finding that Google's 20% ad exchange fee has been above competitive levels suggests that more competition could lead to lower take rates, potentially increasing the share of advertising dollars that reach publishers.

For advertisers, the impact may depend on which remedy is chosen. Google's ad buying tools were not found to have monopoly power, with the court noting that advertisers have many choices outside Google. However, changes to how Google's buying tools interact with selling platforms could affect campaign performance and targeting capabilities.

The timing of any remedies will also be crucial. The government's proposal includes interim measures designed to increase competition while divestiture proceeds, acknowledging the time required to implement structural changes. Google argues its behavioral changes could be implemented within nine to twelve months, while divestiture would take years.

Context of broader antitrust scrutiny

This case represents one of two major antitrust actions against Google. In August 2024, another federal court found Google liable for monopolizing search and search text advertising markets. Together, these cases present significant challenges to Google's core business models.

Google has indicated it intends to appeal the liability decision in this case, stating in its filing that it "respectfully disagrees with this Court's liability decision."

Judge Brinkema must now weigh these competing visions for remedies, balancing the need to restore competition with practical concerns about implementation. Her decision will not only shape the future of digital advertising but may also influence how antitrust law is applied to other technology platforms that dominate their respective markets.

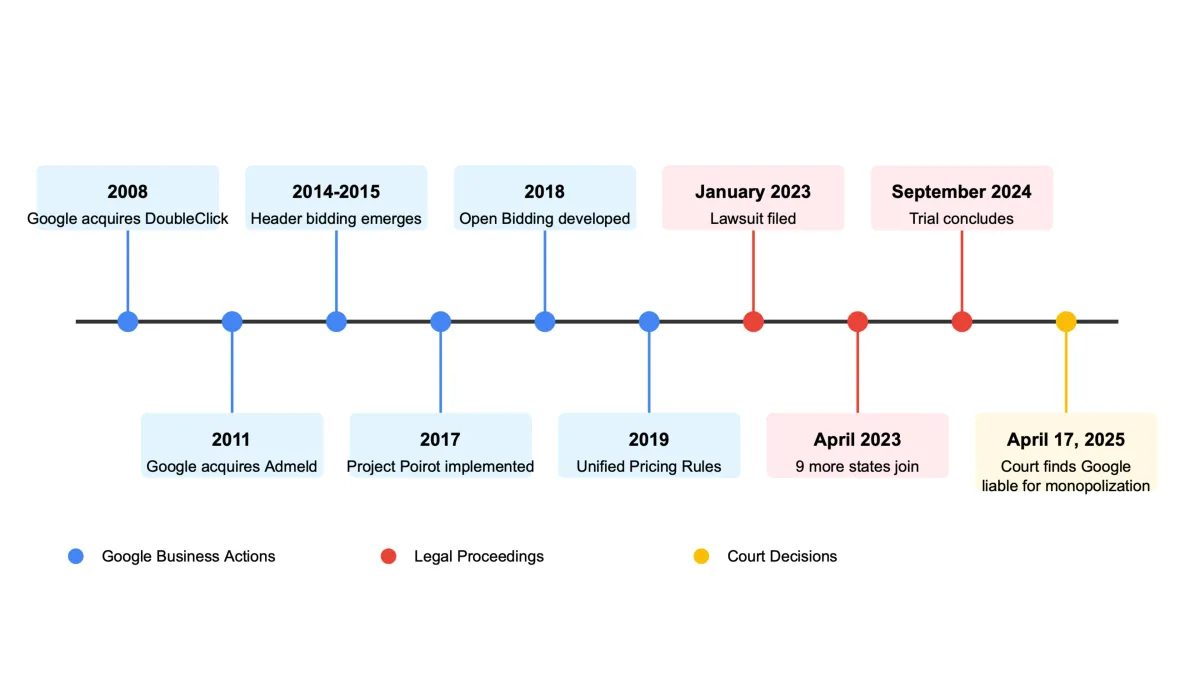

Timeline

- 2008: Google acquires DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, obtaining the dominant publisher ad server and a nascent ad exchange

- 2011: Google acquires Admeld, a yield management tool that helped publishers

- 2014-2015: Header bidding emerges as publishers seek alternatives to Google's advantages

- 2017: Google implements Project Poirot to adjust bids in ways that benefit AdX

- 2018: Google develops Open Bidding as an alternative to header bidding

- 2019: Google implements Unified Pricing Rules, restricting publishers' ability to set different prices

- January 2023: Federal government and eight states file antitrust lawsuit against Google

- April 2023: Nine additional states join the lawsuit

- September 2024: Three-week bench trial concludes

- April 17, 2025: Court issues ruling finding Google liable for monopolization

- May 5, 2025: Both sides submit remedy proposals to the court